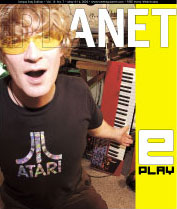

My Fifteen Minutes of Fame

I was

the subject of the cover story for Tampa Bay's local scene magazine, The Weekly

Planet for their May 8th, 2002 issue. I'd seen an earlier article about

my good friends Barely Pink, and suggested to the music editor of Planet that he

do a story on the online indie music scene in the area. Well, he came over to

the house and interviewed me for a couple of fun filled hours, and their photog

shot a couple of gigabytes of photos, they interviewed some other area artists, and

the rest is history:

ePlay

BY SCOTT HARRELL

May 8th, 2002

With MP3.com and other music repository sites, unknown musicians worldwide have a new outlet, a new audience and, sometimes, a new income.

Sitting at the huge computer monitor in the spare bedroom of his St. Petersburg home, stroking the family cat nestled in his lap, Phil Traynor could be your accountant. He's got the pleated trousers, the oversize glasses and the round, unassuming face of a man who finds his reason for being in neatly ordered columns of numbers. But his brightly lit home office isn't strewn with logbooks and stacked paperwork; it's literally jammed with myriad musical instruments and racks of recording equipment. And his PC's hard drive isn't full of spreadsheets and financial analyses -- it's home to various sonic manipulation programs and the tunes that Traynor, a lifelong musician, creates and produces here, before marketing and distributing them via the Internet.

"I'm 37 years old. I'm fat. I'm bald," he says with a laugh. "I'm not packageable in any traditional sense. If I'm going to be any sort of success, it's going to be online. It's going to be purely because of the music."

Traynor is among an ever-expanding throng of musicians turning to home production and the Internet to satisfy creative urges. Relatively inexpensive digital recording equipment and, most important, the mp3 music-file format have spawned a new breed of artist for whom the familiar procedures of independent music -- bands, gigs, pricey studio time -- no longer apply. Via any one of thousands of song-centric Web sites, they make their art available worldwide and interact with a burgeoning online community of pundits and peers.

Traynor spent years kicking around the live-music scene in various jazz and blues combos, working the usual food service and labor jobs to pay the rent. Like the vast majority of creative souls, however, the need for some stability eventually caught up with him. Marriage, a position as a Systems Engineer for Tech Data and the accoutrements of a "real life" beckoned, so he walked away from making music for most of the '90s.

"The regular career started to take off, so I had to shelve (music). I had to get up every morning," he says. "My best friend had a band that I would sub in every once in a while, but other than that, I wasn't playing, wasn't writing, I wasn't doing anything."

When that best friend died suddenly of a heart attack at the improbable age of 34, Traynor was forced to consider life's ephemeral nature, and he embraced his languishing creative gifts once more. Around the same time, another friend who was trying to quit smoking introduced Traynor to some folks she'd met in an online support group. One of them worked for music repository Riffage.com, a now-defunct Internet site where artists could place recorded music for perusal by using the then-newborn format known as mp3 -- basically, a way of compressing and re-coding digital sound files into smaller chunks of data for more efficient transmission and storage.

Traynor uploaded some of his smooth jazz compositions and, as he puts it, "got bit by the bug." His burgeoning interest in the online music community led him to various chat rooms, Web sites and, ultimately, MP3.com, a nascent hub where anyone with a little computer know-how could build a Web page and entice surfers to give their songs a listen.

"It was just a way to get it out there. Maybe a few hundred people will hear me; maybe some guy in another state will say "hey, you wrote a good song,'" Traynor says.

Then, in late 1999, MP3.com initiated its "Payback For Playback" promotion, and began paying artists on its site a small royalty each time their music was downloaded.

"I knew a little bit of the business side of that, so I started to market myself. And I started to get bizarrely successful," says Traynor. "Something happened, and I don't know what it was because I didn't have a lot of confidence in my music. But it just went wild."

How wild?

"In 2000, I made $7,000 just from having my music downloaded."

Seven thousand dollars isn't exactly an annual living wage, but then again, Traynor didn't have to lug a ton of equipment, haggle with a cheapskate club owner or run through "Brown Eyed Girl" a hundred and four times to earn it. He has a great career, a wonderful wife, a nice house and a creatively fulfilling hobby that made him almost as much as a part-time job. And his 200,000-plus MP3.com downloads, while impressive, pale in comparison to some of the numbers racked up by other artists on the site.

"You can make insane amounts of money," he says.

For Traynor, and most unsigned and largely unknown artists, making some money through distributing their work on the Web is a pleasant side benefit. Expressing themselves and making that expression available to others are the primary motivators. Web pages are largely tools for promotion, marketing and communication. Other than mail order or credit card merchandise sales, the chances of a musician's own site becoming a profitable enterprise is pretty much nil. Only a handful of the thousands of hubs, portals and community sites dealing with music actually offer payment for listens or downloads. Of these, only the well-known MP3.com generates the kind of traffic that could potentially translate into substantial royalty payments.

Over the last year, hordes of electronic composers have set up shop on the site with the expectation of income, attracted by some truly spectacular success stories like that of Martin Lindhe. At that time a Swedish web designer (and former Tampa resident) who creates ambient electronic music under the name Bassic, Lindhe was reportedly paid some $70,000 by MP3.com in a year's time. Several Internet and music news outlets covered the story, and his page on the site has logged well more than 5-million listens.

"He got pretty much a head start; he was in it when MP3.com first started and rose up the charts pretty fast," says Jia Huang, who worked with Lindhe during Lindhe's stay in the Bay area. Inspired by Bassic, Huang forged his own online musical identity, NeuralMan, and has made nearly $17,000 since January 2000.

"He kind of opened my eyes to composing music for myself and for others," Huang says. "This is something I enjoy doing, making music and sharing with people, but I'm not making a living."

Numbers like Lindhe's have ushered in a new breed of "serious" MP3.com users, artists bent on wringing every penny possible out of the system. They avail themselves of the site's various promotional opportunities, network constantly with one another in search of new tips and even resort to somewhat shady practices in the name of racking up downloads.

"There are several artists that are doing really well," says Mike Meengs, a veteran Pinellas County musician whose cyber-ego, Sonic, has amassed 275,000-plus listens on his Turtle Bend page. "I can almost guarantee you there are musicians in fairly big bands out on tour right now that aren't making as much money as I am. There are people on tour that are barely breaking even."

Unlike many of the independent artists who reaped big rewards from MP3.com early on, Meengs has only recently begun to see some impressive returns. While he's hit four hundred bucks a month and thinks he'll keep climbing, most of the site's longtime heavy-hitters saw profits dwindle last year to a fraction of their former size. A few blame the explosion of acts clamoring for the attention of a listener pool that grows much more slowly, but the majority of them seem to feel the site itself is responsible for their reduced dividends.

"I would regularly make over $1,000 during Christmas season. This past year, I made, like, $60," says songwriter Stan Arthur. "I got plenty of downloads, but the way they paid the artist had completely changed."

Arthur, who plays drums for Bay area power-pop outfit Barely Pink, originally used MP3.com as a place to post new solo material while he was between bands, and to archive past recorded material of his that was no longer available as product. Some of the tunes he uploaded were seasonal, and every winter his page would be barraged by hits.

Last October, however, MP3.com seriously retooled its "Payback For Playback" guidelines. The wildly fluctuating royalty rate, which in the past had paid as much as five and a half cents per download, was fixed at one-half of one cent. Artists' revenues dropped accordingly. They are required to join the site's Premium Artist Service program, at $20 a month, in order to be eligible for payment; now, a majority of members don't even make that 20 bucks back. Most dissatisfied MP3.com users cite its purchase by French tech/entertainment conglomerate Vivendi Universal (owners of major label Universal Music Group and its subsidiaries) in August 2001 as the point when its artist-friendliness began to erode.

"Until Universal Vivendi bought MP3.com, artists were compensated pretty well. Then, after the sale, royalties were cut to something like a tenth of what they were," echoes Huang. "Once the big corporation came in, it became pretty obvious that the motivation is pure profit."

To be fair, pure profit was probably always the motivation. MP3.com wasn't exactly Uncle Arnie's Used Tennis Racquets before Vivendi came along; it was already a multimillion-dollar endeavor. And however strong the implication that the site was there to fill independent artists' wallets, it never said such a thing. Stan Arthur is less chagrined about the changes at MP3.com than he is amazed at the naivete of musicians who expected a more-or-less free service to make them rich and/or famous.

"Some people got very sour on them. But they never said they were going to do any of that," he points out. "It wasn't ever about the artist; it was about the technology. It was started by a guy who didn't know anything about music."

Meengs fails to see the downside, in any light.

"It's all good. How can you bitch? I'm gonna have the songs up there anyway," he reasons. "I get up in the morning, and it's like hitting a slot machine. Come on, I wanna see a spike."

Other users have found new, ingenious and ethically questionable methods of jacking up their numbers to compensate for lower payments. Large numbers of MP3.com members will congregate off the network and agree to download each other's material on a rotating daily schedule, upping both their hits and their royalty checks. The company officially frowns on such activity and threatens exile for anyone caught trading; however, as more than one user pointed out, big numbers are as good for MP3.com's profile as they are for its artists' royalties.

As heated as the MP3.com controversy has become on message boards and music sites all over the Web, not too many people are leaving the hub in a huff. A high percentage of the company's most vocal and vehement detractors still keep active pages on the site, if only to boast an impressive number of hits or cash the occasional low-digit check. And these pages serve the same primary purpose they always did, money issue or no: They make the independent artist's music and information available to the world.

"I have as much good to say about them as I do bad, and all of the bad stuff has been recent. My overall experience with MP3.com was extremely rewarding," Traynor says. "Without them I wouldn't have gotten anywhere. It financed my studio."

Electronic music is by far the most sought after, discussed and distributed independent genre online. The generation of kids growing up with high-speed Internet access and CD burners has no fear of technology mingling with art, and the vast majority of artists making money and headway online incorporate electronic elements in their sound. Not coincidentally, many of them hold down jobs in the tech sector. Software such as Acid or Fruity Loops allows the computer-literate to generate music of optimal sound quality within the computer itself, with little to nothing in the way of theory or instrumental training.

"There is a tech connection. When you begin to see the possibilities, I think you tend to gravitate to the types of music most conducive to being produced with computer assistance," says Paul Laginess, online musician and employee at independent-artist site Artistlaunch.com. "And if you end up playing it, chances are you end up liking to listen to it as well."

But tastes are always shifting. It's not genre that's fueling this phenomenon; it's technology -- a combination of affordable production tools; the Internet's instant, nearly infinite reach; and the mp3 format's combination of compact cyber-portability and relatively high sonic quality. Ever more affordable home-recording equipment has had recording studio owners worried for years, but what about the music industry at large? Does something as grassroots as a few artists operating outside the previous parameters for fun and profit really have the potential to bring down such a lumbering behemoth?

"If it would get a little more well-organized, it could. Maybe not tear it down," Traynor says. "You can't change the face of an industry that's been around as long as the recording industry has, that drastically and that quickly. But will it cause evolutionary change? It already has."

Adds Arthur: "I don't see online music destroying major labels. Major labels are just eventually going to have to change their whole philosophy."

On the possibility of unsigned artists parlaying an MP3.com presence into a lucrative full-time career, Traynor is, barring a very few notable exceptions, extremely skeptical.

"Not in and of itself. MP3.com is the only one that's paying, and now, they're not paying squat. No, you wouldn't make a living as a songwriter. But you might find ways to market yourself to people who could facilitate a career in the 3-D world," he says.

Huang believes that the recent surge in artists pimping themselves online has made it tough to make anything, much less a living, out of Internet promotion.

"There's an awful lot of electronic music out there," he says. "I really wonder how realistic it is for an artist to make a living online, from downloads and exposure."

Whatever shifts the online music scene causes within the recording industry's creaking bowels, none of these experienced local online tunesmiths sees Internet music distribution reducing the old guard to ashes. At least, not yet. And for most of them, making a few bucks off MP3.com is still just a neat side effect of having their songs out there for anyone with a modem to hear.

"It's more a matter of creativity," says Huang. "Kind of an experiment, just to see if I could."

"Online music is nothing more than a new avenue for delivery. It's a great thing -- instant gratification. You can record a song and mix it in one night, and turn 150 people on to it the next day," Arthur marvels. "It's neat, but I don't see it as much more than that."

For Traynor, it provided a new outlet for an old need, reacquainting him with a creativity once set aside. Plus, he made a few bucks in the bargain.

"It isn't about the money. I've had 200,000 plays, and I made $7,000 online, and that's great. But that isn't the thing that keeps me going. The best thing about the whole deal is, it inspired me," he says. "It brought me back to writing and playing again. I'm doing more now, in terms of creating, than I had done in the previous 25 years."

As a musician who spent plenty of time playing live, he also freely admits something that perhaps the laptop Mozarts haven't yet discovered: Writing tunes, producing them at home, and distributing them online may be fulfilling, but it does nothing to allay that yearning for the stage.

"I'm jonesing for it sooooo bad," he says with a wistful smile. "I joined my church choir. I'm hitting karaoke bars."

©Weekly Planet, Creative Loafing, Inc.

May 8th, 2002

With MP3.com and other music repository sites, unknown musicians worldwide have a new outlet, a new audience and, sometimes, a new income.

Sitting at the huge computer monitor in the spare bedroom of his St. Petersburg home, stroking the family cat nestled in his lap, Phil Traynor could be your accountant. He's got the pleated trousers, the oversize glasses and the round, unassuming face of a man who finds his reason for being in neatly ordered columns of numbers. But his brightly lit home office isn't strewn with logbooks and stacked paperwork; it's literally jammed with myriad musical instruments and racks of recording equipment. And his PC's hard drive isn't full of spreadsheets and financial analyses -- it's home to various sonic manipulation programs and the tunes that Traynor, a lifelong musician, creates and produces here, before marketing and distributing them via the Internet.

"I'm 37 years old. I'm fat. I'm bald," he says with a laugh. "I'm not packageable in any traditional sense. If I'm going to be any sort of success, it's going to be online. It's going to be purely because of the music."

Traynor is among an ever-expanding throng of musicians turning to home production and the Internet to satisfy creative urges. Relatively inexpensive digital recording equipment and, most important, the mp3 music-file format have spawned a new breed of artist for whom the familiar procedures of independent music -- bands, gigs, pricey studio time -- no longer apply. Via any one of thousands of song-centric Web sites, they make their art available worldwide and interact with a burgeoning online community of pundits and peers.

Traynor spent years kicking around the live-music scene in various jazz and blues combos, working the usual food service and labor jobs to pay the rent. Like the vast majority of creative souls, however, the need for some stability eventually caught up with him. Marriage, a position as a Systems Engineer for Tech Data and the accoutrements of a "real life" beckoned, so he walked away from making music for most of the '90s.

"The regular career started to take off, so I had to shelve (music). I had to get up every morning," he says. "My best friend had a band that I would sub in every once in a while, but other than that, I wasn't playing, wasn't writing, I wasn't doing anything."

When that best friend died suddenly of a heart attack at the improbable age of 34, Traynor was forced to consider life's ephemeral nature, and he embraced his languishing creative gifts once more. Around the same time, another friend who was trying to quit smoking introduced Traynor to some folks she'd met in an online support group. One of them worked for music repository Riffage.com, a now-defunct Internet site where artists could place recorded music for perusal by using the then-newborn format known as mp3 -- basically, a way of compressing and re-coding digital sound files into smaller chunks of data for more efficient transmission and storage.

Traynor uploaded some of his smooth jazz compositions and, as he puts it, "got bit by the bug." His burgeoning interest in the online music community led him to various chat rooms, Web sites and, ultimately, MP3.com, a nascent hub where anyone with a little computer know-how could build a Web page and entice surfers to give their songs a listen.

"It was just a way to get it out there. Maybe a few hundred people will hear me; maybe some guy in another state will say "hey, you wrote a good song,'" Traynor says.

Then, in late 1999, MP3.com initiated its "Payback For Playback" promotion, and began paying artists on its site a small royalty each time their music was downloaded.

"I knew a little bit of the business side of that, so I started to market myself. And I started to get bizarrely successful," says Traynor. "Something happened, and I don't know what it was because I didn't have a lot of confidence in my music. But it just went wild."

How wild?

"In 2000, I made $7,000 just from having my music downloaded."

Seven thousand dollars isn't exactly an annual living wage, but then again, Traynor didn't have to lug a ton of equipment, haggle with a cheapskate club owner or run through "Brown Eyed Girl" a hundred and four times to earn it. He has a great career, a wonderful wife, a nice house and a creatively fulfilling hobby that made him almost as much as a part-time job. And his 200,000-plus MP3.com downloads, while impressive, pale in comparison to some of the numbers racked up by other artists on the site.

"You can make insane amounts of money," he says.

For Traynor, and most unsigned and largely unknown artists, making some money through distributing their work on the Web is a pleasant side benefit. Expressing themselves and making that expression available to others are the primary motivators. Web pages are largely tools for promotion, marketing and communication. Other than mail order or credit card merchandise sales, the chances of a musician's own site becoming a profitable enterprise is pretty much nil. Only a handful of the thousands of hubs, portals and community sites dealing with music actually offer payment for listens or downloads. Of these, only the well-known MP3.com generates the kind of traffic that could potentially translate into substantial royalty payments.

Over the last year, hordes of electronic composers have set up shop on the site with the expectation of income, attracted by some truly spectacular success stories like that of Martin Lindhe. At that time a Swedish web designer (and former Tampa resident) who creates ambient electronic music under the name Bassic, Lindhe was reportedly paid some $70,000 by MP3.com in a year's time. Several Internet and music news outlets covered the story, and his page on the site has logged well more than 5-million listens.

"He got pretty much a head start; he was in it when MP3.com first started and rose up the charts pretty fast," says Jia Huang, who worked with Lindhe during Lindhe's stay in the Bay area. Inspired by Bassic, Huang forged his own online musical identity, NeuralMan, and has made nearly $17,000 since January 2000.

"He kind of opened my eyes to composing music for myself and for others," Huang says. "This is something I enjoy doing, making music and sharing with people, but I'm not making a living."

Numbers like Lindhe's have ushered in a new breed of "serious" MP3.com users, artists bent on wringing every penny possible out of the system. They avail themselves of the site's various promotional opportunities, network constantly with one another in search of new tips and even resort to somewhat shady practices in the name of racking up downloads.

"There are several artists that are doing really well," says Mike Meengs, a veteran Pinellas County musician whose cyber-ego, Sonic, has amassed 275,000-plus listens on his Turtle Bend page. "I can almost guarantee you there are musicians in fairly big bands out on tour right now that aren't making as much money as I am. There are people on tour that are barely breaking even."

Unlike many of the independent artists who reaped big rewards from MP3.com early on, Meengs has only recently begun to see some impressive returns. While he's hit four hundred bucks a month and thinks he'll keep climbing, most of the site's longtime heavy-hitters saw profits dwindle last year to a fraction of their former size. A few blame the explosion of acts clamoring for the attention of a listener pool that grows much more slowly, but the majority of them seem to feel the site itself is responsible for their reduced dividends.

"I would regularly make over $1,000 during Christmas season. This past year, I made, like, $60," says songwriter Stan Arthur. "I got plenty of downloads, but the way they paid the artist had completely changed."

Arthur, who plays drums for Bay area power-pop outfit Barely Pink, originally used MP3.com as a place to post new solo material while he was between bands, and to archive past recorded material of his that was no longer available as product. Some of the tunes he uploaded were seasonal, and every winter his page would be barraged by hits.

Last October, however, MP3.com seriously retooled its "Payback For Playback" guidelines. The wildly fluctuating royalty rate, which in the past had paid as much as five and a half cents per download, was fixed at one-half of one cent. Artists' revenues dropped accordingly. They are required to join the site's Premium Artist Service program, at $20 a month, in order to be eligible for payment; now, a majority of members don't even make that 20 bucks back. Most dissatisfied MP3.com users cite its purchase by French tech/entertainment conglomerate Vivendi Universal (owners of major label Universal Music Group and its subsidiaries) in August 2001 as the point when its artist-friendliness began to erode.

"Until Universal Vivendi bought MP3.com, artists were compensated pretty well. Then, after the sale, royalties were cut to something like a tenth of what they were," echoes Huang. "Once the big corporation came in, it became pretty obvious that the motivation is pure profit."

To be fair, pure profit was probably always the motivation. MP3.com wasn't exactly Uncle Arnie's Used Tennis Racquets before Vivendi came along; it was already a multimillion-dollar endeavor. And however strong the implication that the site was there to fill independent artists' wallets, it never said such a thing. Stan Arthur is less chagrined about the changes at MP3.com than he is amazed at the naivete of musicians who expected a more-or-less free service to make them rich and/or famous.

"Some people got very sour on them. But they never said they were going to do any of that," he points out. "It wasn't ever about the artist; it was about the technology. It was started by a guy who didn't know anything about music."

Meengs fails to see the downside, in any light.

"It's all good. How can you bitch? I'm gonna have the songs up there anyway," he reasons. "I get up in the morning, and it's like hitting a slot machine. Come on, I wanna see a spike."

Other users have found new, ingenious and ethically questionable methods of jacking up their numbers to compensate for lower payments. Large numbers of MP3.com members will congregate off the network and agree to download each other's material on a rotating daily schedule, upping both their hits and their royalty checks. The company officially frowns on such activity and threatens exile for anyone caught trading; however, as more than one user pointed out, big numbers are as good for MP3.com's profile as they are for its artists' royalties.

As heated as the MP3.com controversy has become on message boards and music sites all over the Web, not too many people are leaving the hub in a huff. A high percentage of the company's most vocal and vehement detractors still keep active pages on the site, if only to boast an impressive number of hits or cash the occasional low-digit check. And these pages serve the same primary purpose they always did, money issue or no: They make the independent artist's music and information available to the world.

"I have as much good to say about them as I do bad, and all of the bad stuff has been recent. My overall experience with MP3.com was extremely rewarding," Traynor says. "Without them I wouldn't have gotten anywhere. It financed my studio."

Electronic music is by far the most sought after, discussed and distributed independent genre online. The generation of kids growing up with high-speed Internet access and CD burners has no fear of technology mingling with art, and the vast majority of artists making money and headway online incorporate electronic elements in their sound. Not coincidentally, many of them hold down jobs in the tech sector. Software such as Acid or Fruity Loops allows the computer-literate to generate music of optimal sound quality within the computer itself, with little to nothing in the way of theory or instrumental training.

"There is a tech connection. When you begin to see the possibilities, I think you tend to gravitate to the types of music most conducive to being produced with computer assistance," says Paul Laginess, online musician and employee at independent-artist site Artistlaunch.com. "And if you end up playing it, chances are you end up liking to listen to it as well."

But tastes are always shifting. It's not genre that's fueling this phenomenon; it's technology -- a combination of affordable production tools; the Internet's instant, nearly infinite reach; and the mp3 format's combination of compact cyber-portability and relatively high sonic quality. Ever more affordable home-recording equipment has had recording studio owners worried for years, but what about the music industry at large? Does something as grassroots as a few artists operating outside the previous parameters for fun and profit really have the potential to bring down such a lumbering behemoth?

"If it would get a little more well-organized, it could. Maybe not tear it down," Traynor says. "You can't change the face of an industry that's been around as long as the recording industry has, that drastically and that quickly. But will it cause evolutionary change? It already has."

Adds Arthur: "I don't see online music destroying major labels. Major labels are just eventually going to have to change their whole philosophy."

On the possibility of unsigned artists parlaying an MP3.com presence into a lucrative full-time career, Traynor is, barring a very few notable exceptions, extremely skeptical.

"Not in and of itself. MP3.com is the only one that's paying, and now, they're not paying squat. No, you wouldn't make a living as a songwriter. But you might find ways to market yourself to people who could facilitate a career in the 3-D world," he says.

Huang believes that the recent surge in artists pimping themselves online has made it tough to make anything, much less a living, out of Internet promotion.

"There's an awful lot of electronic music out there," he says. "I really wonder how realistic it is for an artist to make a living online, from downloads and exposure."

Whatever shifts the online music scene causes within the recording industry's creaking bowels, none of these experienced local online tunesmiths sees Internet music distribution reducing the old guard to ashes. At least, not yet. And for most of them, making a few bucks off MP3.com is still just a neat side effect of having their songs out there for anyone with a modem to hear.

"It's more a matter of creativity," says Huang. "Kind of an experiment, just to see if I could."

"Online music is nothing more than a new avenue for delivery. It's a great thing -- instant gratification. You can record a song and mix it in one night, and turn 150 people on to it the next day," Arthur marvels. "It's neat, but I don't see it as much more than that."

For Traynor, it provided a new outlet for an old need, reacquainting him with a creativity once set aside. Plus, he made a few bucks in the bargain.

"It isn't about the money. I've had 200,000 plays, and I made $7,000 online, and that's great. But that isn't the thing that keeps me going. The best thing about the whole deal is, it inspired me," he says. "It brought me back to writing and playing again. I'm doing more now, in terms of creating, than I had done in the previous 25 years."

As a musician who spent plenty of time playing live, he also freely admits something that perhaps the laptop Mozarts haven't yet discovered: Writing tunes, producing them at home, and distributing them online may be fulfilling, but it does nothing to allay that yearning for the stage.

"I'm jonesing for it sooooo bad," he says with a wistful smile. "I joined my church choir. I'm hitting karaoke bars."

©Weekly Planet, Creative Loafing, Inc.